Description

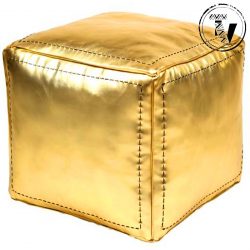

African Hausa Leather Ottoman

– Our round African Hausa Leather Ottoman

is handcrafted with tan, off-white and black leather.

Features the traditional Hausa eternal knot design.

Ottoman has a vintage, worn style and patina.

The creases, small nicks, and other small imperfections create a well-worn

effect that blends seamlessly with any decor and will only get better with age.

The eternal knot

The older and traditionally established motif of Hausa identity, the ‘Dagin Arewa’ eternal knot in a star shape, is used in historic architecture, design, and embroidery.

The Hausa are a diverse but culturally homogeneous people based primarily in the Sahelian and the sparse savanna areas of southern Niger and northern Nigeria respectively, numbering over 70 million people with significant indigenized populations in Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Chad, Sudan, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Togo, Ghana, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Senegal and the Gambia.

The process of leather production for our African Hausa Leather Ottoman

The carefully flayed skin is washed in well-water to remove blood and dung and is then immersed, in a very large earthenware pot, in a solution called toka – a strong alkali solution produced from the ash of’ certain types of wood.

This is equivalent to the European liming process and the skin is quite quickly hydrolysed and becomes very plump. Simultaneously, the hair and other keratinous and non-leather-making proteins arc broken down by this

solution which contains, from previous lots, a small amount of old liquor which the tanner adds to sharpen the new solution. No set amount of old liquor is used and the length of immersion can vary. The skilful tanners, depending

on the time of year (i.e. hot or cold season), will give the skins just the right amount of time so that the hair can be loosened and removed without causing any loss of fibre strength or damage to the grain. The time varies between

a day and a half and five days. At the appropriate moment the skins are removed, washed off and, using the outside of an old wooden corn grinding mortar, the skin is unhaired while held with the knee. A two-handled curved

knife with a very blunt edge is used to press out the loosened hair and roots.

De-Liming

The unhaired skin is again carefully washed and then using the same method, but with a sharp knife, the flesh side is scraped clean of meat and fat left after butchering. Once more the skin is washed and then introduced to a

solution made from a plant, which grows in swampy areas, called koloko. This produces a very mild acidic solution and also contains small quantities of a proteolytic enzyme, papain. As soon as the alkaline skin comes into contact

with this mildly acidic solution it begins to lose its rubber-like plumpness. When the skin is completely neutralized and flaccid it is immersed in a solution containing an infusion of pigeon dung to produce the effect known as

bateing (bateing is the process whereby non-leather-making proteins such as elastin are removed by the action of proteolytic enzymes. It left in the leather they will make it very hard and less flexible). The tanners have to watch

the process very carefully, particularly in warm weather, because the bacteria in this foul solution can very quickly get out of hand and totally ruin the skin. At the appropriate moment the tanners wash off the skin which they test by

squeezing; if the skin is properly bated residual water can be squeezed through the grain from the flesh side. The bate is then sterilized by immersing it in an old tan liquor. The clean, pure white skin is now ready for tanning.

Tanning Process

The local name of the tanning material is bagaruwa; botanical name acacia arabica or acacia nilotica. Other names are garad (India), gabda and sunt (Sudan). The material used is the pod of the tree, which grows prolifically locally. The tree, typical African acacia, with seasonal small yellow blossom, matures in two years and can yield pods for up to ten or twelve years. These are gathered when dry (October to January) and look similar to dried lupin pods, although much bigger, about six inches long. The dried pods are beaten in a corn pestle and mortar (usually by women) and the hard black seeds are separated by winnowing. The remaining powder is then used to make a

tanning solution. This solution is very mild and gentle and the leather is more light-fast than that produced from say, mimosa, quebracho, chestnut, etc. The pod is also used by native herbalists as a cure for dysentery.

Tanning

Using earthenware pots set into the ground, like those used in wash-tub days, the skins are worked in the liquor and from time to time gradual additions of’ bagaruwa powder are made. The skins are worked (chuda) for ten

minutes each hour and left to lie in the solution overnight. It will be observed that after Iying overnight in the strengthened tanning solution the grain of the leather has drawn into the well known pattern. The skins are continually worked and further additions of powder are made throughout the next day, after which they are again left overnight. On the third day a new solution of tan liquor is made and the skins are constantly worked again, when a much lighter and cleaner appearance can be observed. The skins, if cut one or two inches in across the shank or the thickest part (i.e. the neck) would then reveal that the tan had fully penetrated. If not, the process would be continued until this had been achieved. This test does not involve wastage of the skin.

Towards evening, when the main heat of the day has subsided, the leather is removed from the pots, carefully washed off in clean water and all excess water is squeezed out. The skins are then oiled by hand on the grain side, using groundnut oil. This has been prepared by the village women using the farmers’ locally grown product which is crushed into a paste with a stone, the clear oil being drained into a pot. After the oiling the skins are piled grain to grain on rush mats in the shade of a tree and after lying in this manner for two to three hours to allow partial absorption of the oil, the leather is then hung to dry on lines, clothes-line fashion. The slower the drying the better the oil penetration. Next day, the skins are retanned in a fresh bagaruwa solution, carefully washed, and after straining off excess water, hung to dry. In retanning, all the tan and oil stains are cleaned up and the leather then assumes its creamy light-coloured tan shade. During oiling the skins are often adulterated with weight-giving additives by the more unscrupulous tanners. The skins are turned constantly during drying to ensure that this proceeds at an even rate and also to eliminate rope-marks, and so on.

Softening Process

When almost dry and of even colour the skins are hand and barefoot staked in at least six directions. The skin is held across a wooden stake and pulled across the heel to soften the leather – it is a mild stretching and flexing

which releases the fibres which have stuck together during drying. Staking and beating then spreads the oil evenly throughout the skin and on to the fibres so that the leather becomes soft. The skins are then folded in sixes and

beaten over a special stone. The folding is changed from time to time so that all areas of the skins are carefully worked. After being trimmed they are ready for marketing. Most of the skins are sold off in this state, but the very

finest are selected for dyeing. Also, the very poor quality skins, which are unsuitable for export, are dyed into reds, greens, yellows and blues for sale to the desert nomads (i.e. Buzu or Absinawa tribes) who use leather for covering

Koranic charms. Non-exportable skins are also sold in the natural state to Fulani herdsmen for clothing. Most dyeing is still done in the traditional manner, using red dye produced from dawa corn stalks, and blue-black

from the baba (indigo) plant which grows in this area, but some tanners use aniline dyes which are cheap and simpler to use.

More about the goats

The goats are allowed to roam freely during non crop times, i.e. from November or December until early June. During the life of the animal, which is one and a half to two years at the time of slaughter (slaughtering increases

during various Islamic festivals and marriage and naming ceremonies), it could have become scratched by the many thorn bushes abounding in the area. During the rainy season, in order to avoid crop damage, the goats are

kept herded in the farm compounds, at which time they are severely affected by rainy season dermatitis. Many other diseases affect the physical appearance and quality of the skin, making it useless for bookbinding purposes, so the best skins come from the younger, smaller animals. For these reasons leather suitable for bookbinding is probably less than three or four per cent of the total production. Surplus male goats are slaughtered in preference to females. The latter provide many of the large skins which binders often need, but due to regular breeding the skins become over-stretched and loose, which renders them unsuitable. Even a good skin can be ruined by the

butcher’s knife, or, if badly dried when new, putrefaction and grain crack can occur. It will be appreciated that it is extremely difficult for even a faultless skin to survive the many hazards to which it is exposed before being wrapped

around the binder’s raw material!

Our African Hausa Leather Ottoman will complement any decor